Teaching running back flow reads to inside linebackers

During the course of any football season, there's a good chance a defensive coordinator may attempt to defend up to six different types of offensive schemes. Because of this, I teach my inside linebackers in our 4-2-5 and 3-4 defenses how to defend against certain flow concepts rather than specific schemes.

The way we break it down, there are four types of flows:

- Tight flow

- Full flow

- Fast flow

- Split flow

While we generally read the play side guard we're aligned on to identify the direction of the play, once that's recognized, we'll pick up the path of the near back(s). For each of those flows, we use a separate type of block destruction.

RELATED CONTENT: 4 limited-contact drills to drive competition, teach defensive skills

Tight flow

Potential play structure: Dive, trap, iso, fullback belly

Running back path: Downhill, no lateral step

Guard flow: Play side, base or gap block; back side, base or gap block

Linebacker postsnap movement: Attack step, fill open window with force

Block defeat:Play side uses a near-foot, near-shoulder technique, meeting them on their side of the line of scrimmage. Back side uses compress

This type of flow is common in short-yardage and goal-line situations. It’s a clear read for our linebackers, but the key is to attack the lead block on their side of the line of scrimmage. It’s an aggressive offensive scheme, but we need to be the aggressor.

RELATED CONTENT: 4 ways to teach defenders to get off blocks and be in position to make tackles

Our block destruction is a shock, which to us is a near-foot, near-shoulder technique. We don’t use our hands; we feel we need to be thicker than that. We try to win outside, forcing the ball in, but we'll always have a force player to either side of the front side backer. We emphasize being more physical than anything else. It’s a bonus if we’re able to separate and make a play on it. We just want the ball to bubble out.

Full flow

Potential play structure: Inside zone, power, sprint draw

Running back path: Downhill with lateral step

Guard flow: Play side uses gap step away; back side uses pull away

Linebacker postsnap movement: Shuffle and press to next open window

Block defeat: Play side uses compress or shock (based on cloudy or clear), back side uses compress C play with hands to squeeze (constrict) the gap

We see this type of flow more than anything else. The key to this action is to keep the linebackers’ shoulders square. Again, we need to match the action of the back. If their shoulders are squared, so are ours. This is essential because of potential cutback. Nowadays, the inside zone is a cutback play and the power play is hitting in the A gap, so we tell our linebackers if the back’s in the box, you’re in the box. Again, rarely do they have force, so they don’t need to be over the top. We don’t talk about stacking the defensive line; we talk more about tracking the back.

The proper block destruction is a compress technique, which means we'll play with our near shoulder and our near hands. The word compress simply means we'll shorten, not expand any play side gap. If we can’t make the tackle, we'll take our blocker and push the hole. The back side linebacker must play with his hands and try not to come underneath any gap blocks.

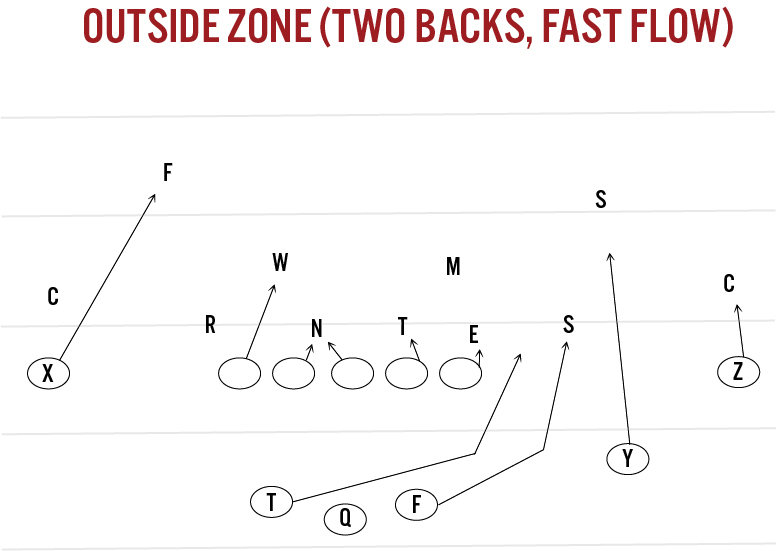

Fast flow

Potential play structure: Speed option, jet sweep, toss, outside zone (stretch)

Running back path: Side look, shoulder perpendicular to line of scrimmage

Guard flow: Wide zone step, bucket step or pull

Linebacker postsnap movement: Open shoulders, get out of the box

Block defeat: Play side and back side linebacker uses dip, rip and run (no contact zone)

Again, we’ll mirror the back. If the back is out of the box, we’re out of the box. Some teams pull that front side guard on these schemes (which makes it easier for us,) but some don't. Either way, we try to cross-face all blocks, constrict our front shoulder level and get running. We try not to use our hands.

RELATED CONTENT: [PODCAST] James Madison defensive coordinator Bob Trott discusses what makes the Dukes successful

This is the easiest scheme to diagnose. Our two interior linebackers can run and not worry about cutback. We’re mainly a quarter’s coverage team, so the cutback responsibility is handled by our backside safety.

Split flow

Potential play structure: Counter trey, halfback counter, fullback counter, split belly, Wing T Sally

Running back path: Misdirection step

Guard flow: Play side uses gap step away; back side pulls away

Linebacker postsnap movement: Shuffle, then rock step

Block defeat: Play side and back side use compress

Finally, split flow is the flow we see the least, unless playing a Wing-T team. Pro teams have gotten away from the traditional Redskin counter trey, but instead pull a halfback or fullback off the ball. To us, it’s the same read.

The key to diagnosing this scheme is what we call "seeing color." To the backside of the play (usually the Will’s read), it’s a simple identification if their guard pulls. If that guard doesn’t pull, and the offense still runs misdirection, they look for any color opposite the play. As soon as that color flashes, they're tacking rock step and pressing the next open window (gap), just like they would in a full flow scheme.

The front side or play side backer is still working their compress technique with their hands and constricting an open gap. Perhaps the biggest concern we’ve had is whether we'll allow our linebackers to come underneath gap blocks. Staying with the principle of playing fast, we tell them if they can press quickly enough, constrict their pads and flatten out, go make a play. I realize this is nowhere near remarkable coaching, but you’ll find some kids can do it and some can’t. In any case, a coach can’t chew them out for making a play.

The benefit of this system is that our linebackers don’t get bogged down with having to know all these various run concepts. We just talk about flow. They had better know which of those four flows were presented in the run that was just used. We all know getting to the point of attack is half the battle of making a play. This helps them to do that.

Mike Kuchar is co-founder and senior research manager at XandOLabs.com, a private research company specializing in coaching concepts and trends. Reach him at mike@xandolabs.com or follow him on Twitter @mikekkuchar.

This is an updated version of a blog that originally published March 31, 2016.